Are you an iconoclast?

Iconoclasts are different from the average person and see the world in a diverse and original way. Gregory Berns discovered that these people's brains are different in three main aspects: perception, fear response, and social intelligence.

BOOKSREVIEWSNEUROSCIENCEINNOVATION

Ligia Fascioni

7/14/20254 min read

That's a tricky question, huh? I'll give you a hint – until some time ago, I had no clue if this was something you eat or drink.

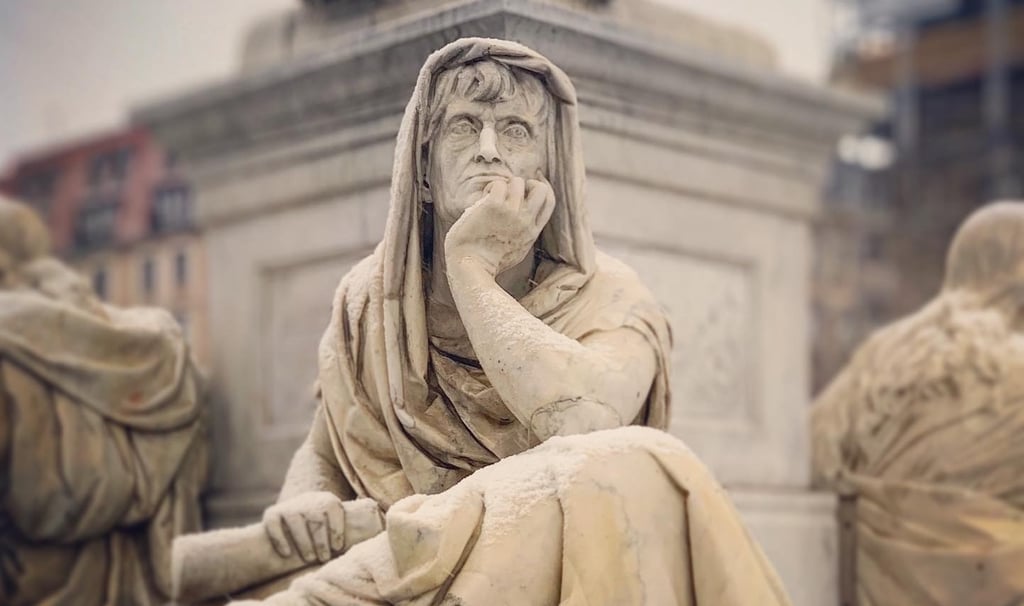

Here we go: iconoclast literally means destroyer of icons. The word dates back to 725 AD, when Leo II, emperor of Constantinople, destroyed the golden icon of Christ installed at his palace gates. An iconoclast doesn't respect symbols, idols, religious images, or any kind of social convention or tradition.

An iconoclast believes that nothing and no one is worthy of worship or reverence.

The guy who dug this up from ancient times and brought it to our contemporary world was neuroscientist Gregory Berns, with his excellent book "The Iconoclast."

Berns updates the concept when he says that an iconoclast is an unusual person who interprets reality differently and does what common sense judges impossible to do. In other words, iconoclasts are innovators, that breed of people who change the world and turn everything we know upside down. These folks aren't always easy to deal with, but they're the ones who make civilization move forward.

Iconoclasts are different from the average person and see the world in a diverse and original way. Gregory Berns even discovered that these people's brains are different in three main aspects: perception, fear response, and social intelligence.

1. Perception

Iconoclasts perceive the world in a way that other people don't usually even imagine. The explanation for this is that the brain has a fixed energy expenditure and can't spend more when it has to perform a more complicated task. To solve this, our gray matter has some tricks that make it more efficient: one of them is labeling everything that comes its way, in a scheme called predictive categorization (a scientific name for prejudice).

Here's how it works: to avoid being saturated with information, the brain infers what it's seeing – it spots just part of the scene and immediately mutters: "ah, I already know this, it's a seahorse doing a handstand." So our brains choose some parts they find more interesting and ignore the rest. This saves energy and works great day-to-day, but it ruthlessly destroys all our imagination and creative capacity.

So one way to outsmart Mr. Lazy Thinking is to confront the perceptual system with something it doesn't know how to interpret, since it's never seen anything like it before. This forces the discarding of usual categories and the creation of new ones.

Dr. Berns recommends travel as a great opportunity to present unusual things to our brain and suggests that meeting new people, ideas, flavors, images, languages, words, and habits different from ours helps a lot to destabilize established patterns of perception (and deconstruct comfortable prejudices).

By the way, Gregory warns that the more we try to think differently, the more rigid the statistical categories installed in our heads become. The only way to tame this thing is precisely by bombarding the stubborn thing with unprecedented experiences.

Iconoclasts love feeding their brains hungry for novelty and don't usually fit what they see into categories they already have; they create new ones. That's why they can perceive the world without falling into the temptation of labeling things the way everyone else does. This is how they discover new metaphors, functions, ideas, and ultimately innovate.

2. Fear response

Fear makes us feel bad, insecure, scared. It distorts our perception, paralyzes us, and prevents us from creating.

Every human being responds pretty much the same way when subjected to a stressful situation: blood pressure rises and the heart races; the mouth goes dry and we start sweating; fingers tremble, voice wavers, and some people even feel dizzy.

Neuroscientists have identified 3 basic types of fear: fear of the unknown, fear of failure, and fear of looking stupid.

Iconoclasts also feel fear, but unlike the masses, they manage to prevent their perception from being distorted; since they think differently and experiment with other viewpoints, the whole thing becomes less terrifying. There's always a solution, hope, or another way to face the risk.

Check out this quote from Henry Ford, one of the greatest iconoclasts of all time:

"Those who fear the future, who fear failure, limit their activities. Failure is only the opportunity to begin again, with doubled intelligence. There's no shame in honest failure; there is in fearing to fail."

3. Social intelligence

Many good, creative, and fearless people have already gotten into trouble because of their inability to sell their ideas to others. Successful iconoclasts don't, because they have this talent very well developed.

It's basically this last aspect that differentiates the story of a Van Gogh (who died alone, in poverty) from a Pablo Picasso (whose assets were valued at $750 million when he died in 1973).

Berns explains that to sell an idea, the iconoclast needs to develop two things: familiarity and positive reputation.

Familiarity is established through productivity and exposure; with a good network of contacts, the person becomes known both for their work and their ability to impact social groups with their opinions.

Successful iconoclasts, like Picasso, are like a network node; they both influence groups and connect them. Van Gogh, despite being brilliant, had low productivity and an even smaller number of friends or acquaintances. He was an isolated genius, a sure recipe for misunderstood art and wasted iconoclasm.

Building a good reputation makes people get used to the iconoclast's ideas, making them seem less scary and risky. For the iconoclast to actually sell their ideas and change the world, they need to make themselves trustworthy.

Gregory Berns discusses various cases of iconoclasts unknown to the general public and others who became celebrities, like Steve Jobs.

Conclusion

The great irony of it all is that, being so talented and special, these people achieve the unthinkable: from iconoclasts, they transform into icons, true objects of worship for their fans.