There is no thinking outside the box

You've definitely heard the famous expression "think outside the box." It's almost become a law, right? Those who don't think outside the box can't be creative or innovative. Well, that's actually the biggest nonsense of recent times.

INNOVATIONBOOKSREVIEWSIDEAS

Ligia Fascioni

4/21/20254 min read

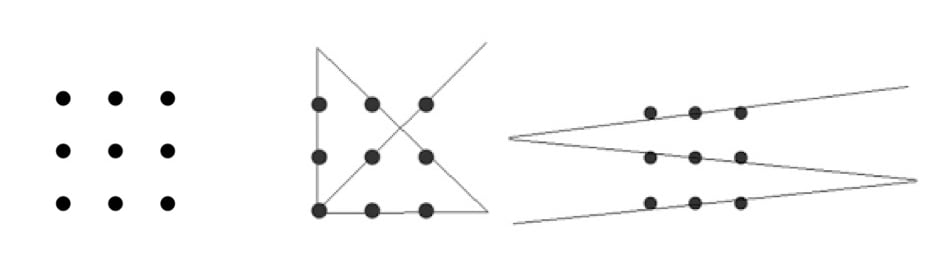

The study found that 80% of participants couldn't find a solution because they remained stuck within the imaginary boundary. The research team didn't hesitate to create this kind of "law" stating that to be creative, one needed to think "outside the box."

That's when creativity gurus started using the expression (although it began in the 70s, you could say the idea "went viral").

Does it make sense?

Everyone kept repeating the mantra until researchers decided to verify the story and conduct another experiment using the same nine-dot puzzle. For the first group, the test was presented exactly as Prof. Guilford had done. For the second group, they were told the solution involved thinking outside the imaginary square – basically giving away the hint that almost solved the puzzle.

The result? In the first group, as expected, only 20% of participants solved the problem. The surprise came with the second group: only a disappointing 25% managed to find the solution.

In other words, repeating the mantra "I must think outside the box" or even trying to "think outside the box" makes no difference at all. The box is us – there's no way to get out of it. The box is our repertoire, our set of knowledge and experiences.

Make the box bigger

The solution isn't to get out of the box but to expand it, make it richer, equip it with more tools. And better yet, connect it to other boxes, forming a network.

The authors argue that you're more creative when you explore the familiar world more deeply. And they go further; they developed a method and applied it in various companies worldwide.

This idea of thinking inside the box comes from another book called "The Closed World," published in 2000 by Roni Horowitz. This author argues that if there's a solution to a problem, it will be more creative if it uses elements from the problem's "closed world." This perfectly aligns with the concept used in design thinking, where the solution and problem exist within the same space; you just need to identify which is which.

And it makes sense; artificial intelligence researcher Dr. Margaret Boden states that "constraints, rather than opposing creativity, make creativity possible." Removing all constraints removes creative capacity (I already wrote about this ten years ago, see!).

The myth of brainstorming

Another myth debunked in the book is about brainstorming; after becoming trendy and being used even in high schools (the concept was born in 1953 by advertising executive Alex Osborn in his advertising agency), studies showed that the method offers no advantages over individual proposal generation; furthermore, ideas generated with this method are fewer and of lower quality compared to individual work or small groups.

Template for creativity

But returning to the method developed by the researchers, they created five interesting techniques within what they call the Template for Creativity:

Subtraction: involves removing an essential component of the product or concept and identifying who would see value in the result. As examples, they cite fabric softener, which was created in an exercise where the essential cleaning element of soap was removed. Or IKEA, where furniture assembly (an essential item in most stores) was also removed. Or Sony's Walkman, which didn't have a recording function. Or electronic bank terminals, which removed human tellers from the service process. They don't mention it in the book, but what is Uber if not a transportation company without vehicles? And Airbnb?

Division: involves dividing the object or process into multiple parts and rearranging them in a different, new way. As examples, they cite traffic authorities in Ukraine who divided the functions of a parked car into parts and concluded that if a driver parked in a prohibited area, they only needed to isolate one part (in this case, the license plate), taking it to a central office. The plate (and total function) would only be restored with payment of the fine. Or the split-type air conditioner, whose compressor was isolated and installed in a place where it would cause less disturbance. Or prepaid cell phones, where people pay before using (unlike previous methods).

Multiplication: involves multiplying some component of the process or function, even if seemingly unnecessary. This is the technique that leads to multiplying the number of wheels on a bicycle temporarily while someone is learning; or those video sub-screens that allow a person to flip through other channels while watching a program on TV, for example.

Task unification: involves combining two or more different elements of processes or objects so that the combination has a new function. Examples include makeup that incorporates sunscreen, mobile advertising on vehicles, or cell phones with geolocation functions.

Attribute dependency: involves relating two or more elements of innovative products or processes that apparently have no relationship with each other. For example, windshield wipers that change speed according to the amount of rain, or apps that provide information about restaurants and stores when the user approaches an area; in other words, one function depends on information from the other. The application depends on geolocation; the windshield wiper depends on the rain sensor.

Each technique is detailed with many real examples. I found this tool could be a very interesting way for us to rethink the way we solve problems and generate new ideas.

Conclusion

For my part, I found the exercise of breaking down a process or product into elements and then making various combinations quite useful.

I could already see that the practice yields many interesting things. Maybe it's your case too?

From now on, every time you hear the expression "think outside the box", you will think of this book. And you will doubt the ready-made phrases that we hear around, which is very healthy.

You've definitely heard the famous expression "think outside the box." It's almost become a law, right? Those who don't think outside the box can't be creative or innovative. Well, that's actually the biggest nonsense of recent times.

With help from Drew Boyd and Jacob Goldenberg, authors of the excellent "Inside the Box: a proven system of creativity for breakthrough results," I'll explain why.

where it all began

First, let's discover where this box story came from. According to the authors, it all started with a creativity study led by Prof. J.P. Guilford, based on the nine-dot puzzle. You probably know it, but here goes: the challenge is to connect all 9 dots using only four lines without lifting your pencil from the paper. People tend to think the solution must be within the imaginary square where the dots are placed, but the solution (there are several, actually) involves "going outside that square."